All That May Do His Rhyme: An Intro (and a Farewell) to Roky Erickson

One of the best movies to touch on music obsession as personal expression, Stephen Frears’ High Fidelity, begins fittingly with a turntable spinning. A needle is dropped purposefully onto a record. Underneath the homey crackle and pop of the ancient vinyl, the 13th Floor Elevators garage rock classic, “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” begins.

Four lone, unaccompanied guitar chords pound through. Soon after, the drums and a bizarre alien hum (actually an electric jug) kick in. Then comes the vocal—a snarling, soaring, utterly out-of-control wail that suggests a bobcat on mescaline, tangled in barbed wire and fighting for its life. The antiquity of that sputtering vinyl only intensifies the feeling that the voice you’re hearing emanates from somewhere gloriously, chillingly not of this earth.

It’s the kind of tooth-rattling rock and roll howl from which cult worship is born, and the generator of that magnificent noise, singer/songwriter/guitarist Roky Erickson, left this planet for real on May 31. Even given the harrowing flurry of musical heroes who’ve shuffled off this mortal coil lately, the loss of Roky feels personal for me—like my sweet, eccentric, visionary holy fool of an Uncle has passed away.

His rise, fall, and rebirth play like fodder for a fictional movie. And the resonance of the man’s life story goes a long way towards explaining why so many of his fans—myself included—felt an almost familial empathy and protectiveness towards him. Those emotions are almost as instinctual as the thrill, awe, and exhilaration generated by his music. Almost.

Roky Erickson and his fellow musical explorers in The 13th Floor Elevators were one of the first bands in the ‘60s to literally spike garage rock with a hearty dose of psychedelia: The band endorsed (and sought spiritual enlightenment through) the liberal use of psychedelics, most prominently LSD. But in contrast to the ornate production and flower-power glee that comprised most ‘60s psychedelic rock, The Elevators’ path to the sonic cosmos was rife with a visceral sense of danger.

Electric jug player/informal band leader Tommy Hall labeled the band’s music psychedelic rock. With hindsight, psychedelic punk fits the music more aptly. The force of the Elevators’ near-chaotic playing, the raw production on their records, and Roky’s singular voice—an ear-scraping rock howl one minute, an otherworldly zealot’s trill the next—suggested a shaman offering a crudely recorded play-by-play as the doors of multiple dimensions burst open in front of him.

When the Elevators left their native Texas to play in San Francisco, that city’s counterculture embraced them. Fellow Texan Janis Joplin, herself a denizen of SF’s counterculture by that time, almost joined the band. And it’s probably no coincidence that the Haight-Ashbury scene’s mid ‘60s shift from acoustic folkiness to loud and lysergic rock occurred right after The 13th Floor Elevators first tore through town.

But the musical and literal highs came at a heavy cost for Roky Erickson. With LSD and other hallucinogens forming key components in the Elevators’ psychedelic stew, Erickson himself purportedly dropped some 300 hits of acid during those years.

The band’s active endorsement of said drugs also put local authorities on the alert. In 1969, Roky was busted for possession of a single marijuana joint, and rather than face the Draconian prison time exacted for a criminal charge in Texas, Roky’s attorney copped an insanity plea. The 13th Floor Elevators fragmented, and Roky wound up committed to Rusk State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. He was subjected to daily shock treatments and Thorazine doses, and was housed in a nightmarish environment alongside child rapists and murderers. After his discharge two years later, he was never the same.

A diagnosed schizophrenic, Roky Erickson spent the next two decades in a state of abject psychosis, in and out of mental institutions and eventually living in poverty in a tiny hovel of an apartment in Austin, Texas. His mother Evelyn became his de facto guardian, and her extreme phobia over psychiatrists, drugs, or chemical treatment of any kind put an indefinite hold on any sort of therapy for her eldest son.

Happily, Roky’s youngest brother Sumner (a principal tuba player for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra) fought for—and won—guardianship of his older brother in the early 2000’s, and a carefully-controlled regimen of drug-and-psychiatric therapy worked wonders.

For all the strides he’d made, the notion of him hitting the road and touring still seemed like a pipe dream in the early Oughts. So when Roky and his longtime backing band, The Explosives, played Bumbershoot in 2007, it wasn’t just another old-school rocker hitting the comeback trail: It was pretty much a bloody miracle.

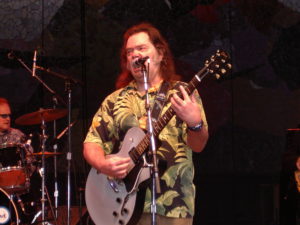

Roky Erickson, raising demons live at Bumbershoot 2007. (photo by Tony Kay)

I had the good fortune to see Roky play live that afternoon. He looked happy, sounded great, and had no right to be as amazing as he was, marshaling the most corrosive of rock and roll growls in front of a Mural Amphitheatre lawn packed with several hundred fans.

The second time I saw him was in 2010, as part of the City Arts Music Festival that year. The 2007-model Roky was clean-cut and smiling; The Roky Erickson I saw in 2010 was full-bearded, hirsute, and almost menacing, often turning his back to the capacity crowd at Neumo’s as he played. But he still sounded like a force of nature, and the younger musicians backing him lent a darker, swampier tone that impeccably fit his material.

Roky Erickson at Neumos, 2010. (photo by Tony Kay)

The last decade of his life Roky Erickson toured, recorded an album with Okkervil River, collaborated with The Black Angels on live stages and in the studio, and enjoyed a reputation in Austin, Texas as one of the city’s most beloved musical elder statesmen. It was a happy way to spend his golden years to be sure, but his passing still stings. Godspeed, Bleib Alien.

Roky Erickson 101:

Even during some of his lowest psychological ebbs, Roky Erickson remained creatively prolific, recording frequently throughout the last two decades of the twentieth century and beyond. If you haven’t heard much or any of Roky’s music, the below releases represent a pretty choice intro into his catalog.

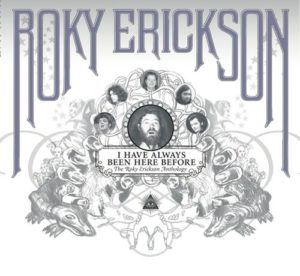

I Have Always Been Here Before: The Roky Erickson Anthology (Shout Factory, 2005)

This exhaustive two-CD set includes Roky’s first recorded rock song (“We Sell Soul,” cut with his pre-Elevators band, The Spades), almost a dozen 13th Floor Elevators tracks, and copious selections from his finer solo efforts. It’s out of print and pricey, but a bit of burrowing on Ebay can unearth a copy that won’t bust your wallet. A goodly share of these songs can also be found on Spotify and iTunes.

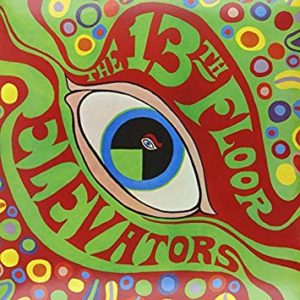

The 13th Floor Elevators, Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators (Collectables, 1966) and Easter Everywhere (Collectables, 1967)

The 13th Floor Elevators, Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators (Collectables, 1966) and Easter Everywhere (Collectables, 1967)

The Elevators’ first two albums still rock like hell, and their low-fi take on mind-expanding psychedelia has aged remarkably well. These records impacted the psychedelic revival of the eighties, grunge rock (Kurt Cobain was an avowed Elevators fan), occasional Roky soundalike Jack White, and the modern neo-psychedelia of The Black Angels (who frequently played live with Roky in the last few years of his life) and the Brian Jonestown Massacre.

Roky Erickson and The Aliens, The Evil One (Sympathy for the Record Industry, 1980/2002; Light in the Attic, 2019)

Roky Erickson and The Aliens, The Evil One (Sympathy for the Record Industry, 1980/2002; Light in the Attic, 2019)

Roky’s post-Rusk output is obsessed with horror-movie and demonic lyrical imagery, but this is no mainstream career rocker name-dropping old chillers a la Rob Zombie or Glenn Danzig: Roky’s embrace of horror movies on tracks like “If You Have Ghosts” and “Creature with the Atom Brain” definitely sounds like a man using the dark escapism of fictional horror to deal with his own very real demons.

Don’t Slander Me (Pink Dust Records, 1986; Restless Records, 2005; Light in the Attic, 2013)

Don’t Slander Me (Pink Dust Records, 1986; Restless Records, 2005; Light in the Attic, 2013)

Don’t Slander Me still showcases Roky’s well-established penchant for the macabre (dig his malevolent cackle in the middle of “Burn the Flames”). But much of the record stands as his most accessible effort, with hellzapoppin’ rock tracks like “Haunt” and “Can’t be Brought Down” sharing space with some lovely pop songs like “Starry Eyes” and “Hasn’t Anyone Told You.” And if you need a textbook example of rock singing at its most scorchingly intense, look no further than Roky’s vocals on the title track.

Never Say Goodbye (Emperor Jones Records, 1974/1999)

Never Say Goodbye (Emperor Jones Records, 1974/1999)

While he languished in Rusk and other mental institutions in the early seventies, Roky Erickson continued to write and play music: Several times, his mom Evelyn snuck in a tape recorder, committing spare acoustic tracks to cassette. You’d think that the results would be the worst kind of slipshod barrel-scraping, but Never Say Goodbye contains several incandescent pop and folk diamonds in the (admittedly very) rough.

The opener, “Unforced Peace,” reaches for universal tranquility with quiet resolve and total lucidity to rival John Lennon at his finest, and you will never hear a love song more purely beautiful and stirringly honest than “I Love the Living You.” Like many of Roky’s other releases, Never Say Goodbye is out of print, and it’s extremely rare—as of this writing, you can’t find it on iTunes, Spotify, Amazon or Ebay—but it’s infinitely worth seeking out.

Roky Erickson with Okkervil River, True Love Cast Out All Evil (Anti Records, 2010)

Roky Erickson with Okkervil River, True Love Cast Out All Evil (Anti Records, 2010)

If you’ve followed along to this point and listened to any of the above recommendations, it’s impossible not to be powerfully moved by Roky’s final full-length release of original material. Several of Never Say Goodbye’s rough cuts are fleshed out and given rich Americana texture by Austin indie band Okkervil River, with Roky singing most of the songs in a worn but affecting croon that bears the marks of every minute of a life lived–for good and for ill.

Taken as a whole, the album’s a powerful autobiography that’s almost uncomfortably, nakedly vulnerable as well as abidingly hopeful. Kudos to Okkervil leader Will Schiff, who crafted a legit tapestry by bookending the album with ancient recordings of a younger Roky. And if Schiff’s eloquent, heartfelt liner notes don’t have you forcing back tears, there’s something wrong with you.