When you Google, “Who are the biggest pop stars in the world,” you get the names of four womxn artists: Taylor Swift, Beyonce, Lady Gaga, and Ariana Grande. Yet the music industry is still overwhelmingly run by white men, particularly when it comes to areas like music production and composition.

According to a report from USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, entitled “Inclusion in the Recording Studio?,” which looked at 700 songs from the Billboard Hot 100 and seven years of Grammy nominations, only 12.3% of songwriters were female. Only 2% of producers across 400 songs were female.

While the report cited examples of discrimination, male gatekeeping, and lack of representation as major factors for the imbalance in the industry, it’s clear from contemporary research and discussion with many women in music today, that these challenges begin long before playing they play their first professional gig.

In fact, especially for male-dominated industry roles like production and composition, issues of music industry inequity and misogyny often arise from the second womxn enter their academic programs.

For instance, when Seattle-based musician and audio engineer Natalie Bayne was in school for engineering at California Institute of the Arts in San Francisco, she was the only woman in the entire program.

“It was all men, all the teachers were men, and there were just no other women anywhere in sight and it was really overwhelming,” said Bayne.

Bayne defined how this environment was overwhelming and unfair in two key ways—firstly, she had to work faster and harder and smarter to get ahead because the class was so heavily shaped by the male experience, and she had to learn how to deal with sexist commentary and expectations in order to have access to the same opportunities as the male students.

“I found that even in intro classes there was this boy’s club attitude of we already know the basics,” said Bayne. “I think there’s this male culture of getting started in music really early, like their dads showing them how to do stuff. So, a teacher would take a gauge of the room, like, who knows how to set up this kind of thing, and even the guys were like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah” and they’d all act like they knew what it was, so [the professor would say] “Ok, we’re going to jump ahead then.”

Bayne said that she felt “stupid” and “embarrassed” to ask questions because of this, and instead would be forced to research and learn about the subject on her own after class.

“I had to go back and work twice as hard trying to figure things out because it was kind of this, I felt like I was already behind the curve when I started and that was really tough,” she said. “Plus, you had to be buddy-buddy with all the bros and it was a very uncomfortable situation sometimes. I felt like I couldn’t stand up to them, I felt like I had to be one of the guys in order to get by. Like laugh at the sexist jokes.”

But, Bayne stuck with it, rose to the top of her class, and was the one student in her program hired to work as a studio recording teacher for the school. But even then, she found her male peers could only justify her success with sexism.

“There was kind of a lot of anger from the men who didn’t get the job and there was a lot of talk of, ‘Why did she get the job? Did she get it just because there aren’t any other women? Did she get it because some instructor likes her—as more than a friend?’”

Other womxn production students had similar experiences. Even while attending a non-institutional school for music producing in L.A., music producer Mari Sullivan felt that other students “assumed I know less because I’m a female. [They thought] I was just a vocalist,” she said.

In the composition world, it can be quite similar, and even worse in some ways. There’s a very long history of the punishing and erasing women composers in the classical world, especially, and those attitudes continue to shape how composition is taught in music institutions. The Smithsonian Magazine reported on this phenomenon in 2016:

“There are many painfully under-appreciated female composers who were undoubtedly great. These forgotten women achieved artistic greatness despite the fact that for centuries the idea of genius has remained a male preserve; despite working in cultures which systematically denied almost all women access to advanced education in composition; despite not being able, by virtue of their sex, take up a professional position, control their own money, publish their own music, enter certain public spaces; and despite having their art reduced to simplistic formulas about male and female music — graceful girls, vigorous intellectual boys.”

Though it’s definitely better for womxn now than it was in 1800, challenges persist for womxn composers in all genres today and this trend seems to start in they are labeled and taught in music school environments.

“I am a writer and a singer, and I’ve been a composition major at Cornish College of the Arts for three years now,” said one Cornish College of the Arts student who asked to remain anonymous. “At Cornish, what is reflected is all the female writers are labeled or self-identify as ‘songwriters,’ while all the male writers identify as ‘composers.’”

The very act of calling women something different ostracizes them from typical composition roles, and reveals an incredibly sexist and elitist view of womxn’s potential in the field.

“Every time I’ve signed up for a composition class, people have asked me, ’do you realize we’re going to be composing? We’re not writing lyrics,’” the Cornish student said, noting that she knows exactly what she wants to do and learn.

This student also mentioned that the Seattle-based music school made a rule a few years ago that teachers need to teach about “at least one woman composer,” but that the mandate fell through when many male teachers complained that the request was, “too hard.”

In response to these sorts of limitations and inequities, women often feel unwelcome in the production and composition tracks, and switch programs. Meanwhile, those who do remain in production and composition are compelled to advocate and create a way for the next generation, while also tackling their own artistic careers.

“I feel like it’s totally changed my intentions in working in the music industry. Of course, when you start doing music its almost always because you’re writing your own and you want to drive your own music forward, and that’s still really important to me as an artist, but I almost feel like it’s more important right now to educate other women and level the playing field,” said Sullivan.

Along with working on her own projects and producing others, Sullivan has begun hosting a weekly meet-up of women producers, a space where women can feel comfortable enough to call themselves producers and ask questions. She is also currently teaching a women’s-only class about the music production software Ableton at the Vera Project in Seattle.

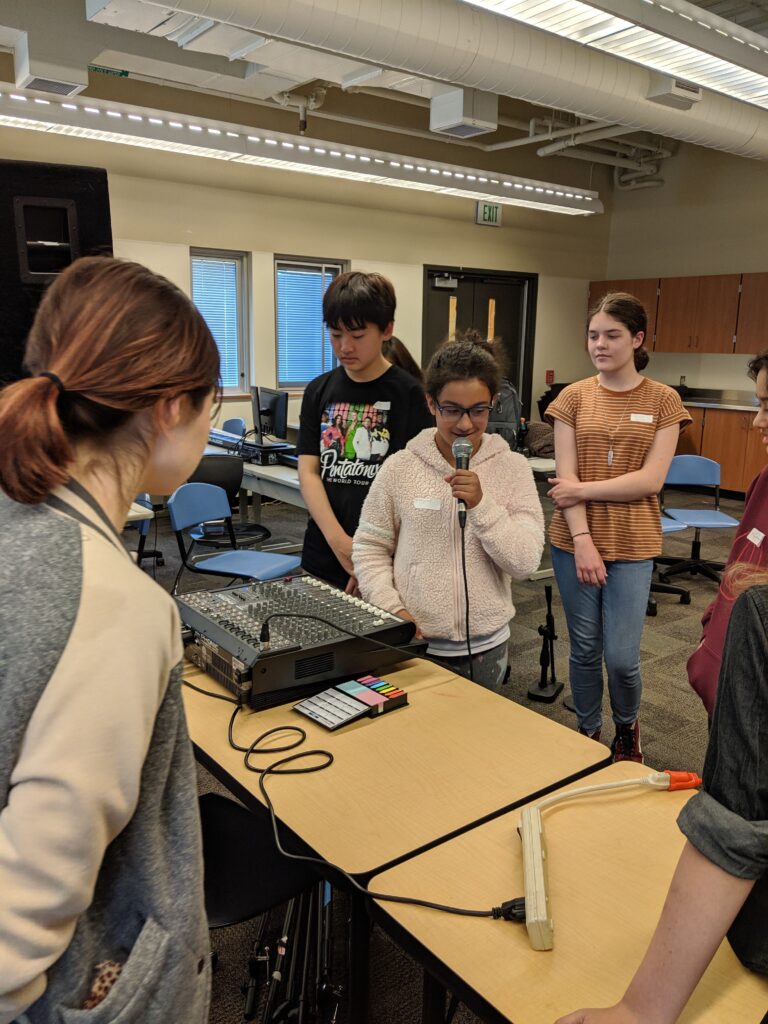

Likewise, Natalie Bayne co-founded The Fifty-One, a Seattle-based audio engineering school for girls in 2014. The Fifty-One holds classes at Seattle Girls’ School, throughout the King County Library System and in some Seattle-based juvenile detention centers.

“The current number of music producers/engineers in the industry is 98% male so we want to use that number—the 51%—as our goal ultimately. And the way we do that is we start with young kids. We really want to make a space where girls and underrepresented groups feel welcome and they feel safe and confident to take risks and to make mistakes,” said Bayne.

According to Chelsi Gorzelsky, educational director at The Fifty-One, “I just want to show young people that careers in the recording arts is a viable option, and that women and non-binary people belong in the space too.”

As for the student from Cornish College of the Arts, she says that the limits that many have imposed on her in the composition program have influenced the way she feels about life after music school.

“I get told a lot, it’s really hard to have a family and be a musician. Or people assume I’m going to be a music teacher [because I’m a woman musician.] For that very reason, I did not want to be a teacher. I was deeply offended by that,” she said. “But, it’s really interesting, because I’m looking at a Masters program in teaching… I wonder if I would’ve considered the teaching path earlier if there hadn’t been all that outside pressure,” she said.

Overall, the “masculine aesthetic”—like being the loudest, the most technical, and competitive—is usually what’s rewarded most in music school programs. This then shapes the industry in negative ways. By refusing to work with narratives and sounds outside the male aesthetic, the music industry stunts its ability to reach a larger market and reduces the amount of the tools it can use to create fresh and exciting music.

“Womxn are going to bring a different lived experience [to their art],” said Bayne. “You’re going to get different work. It’s going to sound different, feel different—because it’s coming from [somewhere] different.”